Two Different Worlds Coming Together

Clearly, data center appetite and demand for power exceeds what utilities can currently provide, both from a capacity and transmission standpoint. In most cases, what the data center industry is asking for doesn’t exist — it needs to be built.

Utilities and data centers also operate at entirely different speeds. Data centers often are backed by huge venture capitalists and investment funding to meet the ever-increasing traditional data center demand and the currently insatiable AI needs. Data center owners, developers and operators with available capital investment dollars make decisions very quickly and expect their partners to move swiftly on their projects. Conversely, utilities must seek the permission of their regulatory public utility commission (PUC) to build any new generation, forced to plan in terms of years and are continually scrutinized by the PUC, activists and other local influencers.

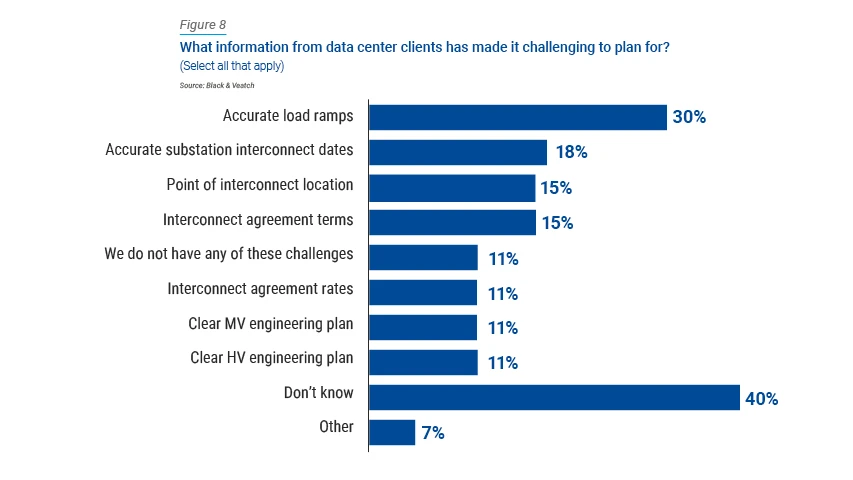

The bottom line: the two industries have fundamentally different DNAs and must find a consistent, meaningful way to communicate and coordinate, especially as the escalation in demand is in early stages. As AI and digital commerce continue to grow, the demand for co-location and data centers will only intensify. Some utilities have set up data center committees or have special team members to deal with the distinctive nature of data centers, but not enough utilities are set up with this purposeful structure.

Download the Report